This article is a short outline of what I see as the macroeconomic effects of a possible continuation of weakness in crypto financial markets. The direct effects would be small, although weakness in crypto is interleaved with the fortunes of the tech sector. It is certainly possible that all risk assets will be under pressure if the economic situation deteriorates, so crypto might be akin to the canary in the coal mine — a signal of other dangers.

I end with a discussion of so-called “stable coins.”

No, I Am Not Predicting a Collapse

I do not trade crypto, nor do I have any interest in doing so. Although I view the space as infested with scams, I do not believe that life is inherently fair and that prices must crash as a result of this. There is obviously a shake-out happening of the weakest crypto assets, and all I am interested in here is discussing the effects of a hypothetical extrapolation of this trend.

Correlation And Canaries

The “technology” sector has one interesting characteristic — there is a large group of investors that mainly invest in tech. Individuals might differ on which securities they hold, but as a group, they are all in the same baskets of stocks. The issuers of tech “securities” then align their issuance to match the demand of these investors, and they are able to support asset prices at valuation levels that appear ridiculous when compared to other sectors.

This behaviour creates volatility — the herd can drive prices up, at the cost of the entire sector being whacked if a liquidation event occurs. To what extent investors borrowed against their positions, they will face a margin calls at the same time.

If the global economy deteriorates due to factors like the commodity price shock and supply chain disruptions due to the lockdowns in China, past history suggests that risk asset prices will also tend to get cut down. Crypto losses would be part of this process. The discussion here is whether it is possible for crypto assets to enter a bear market without taking the real economy with it.

Crypo Industry Not That Large

The reason not to be concerned about crypto as a stand-alone trigger for a recession is the the limited footprint of the industry in the real economy. The main effect would be a reduction in employment and advertising spending. However, these firms are not major employers, and it is unlikely that the jobs would disappear instantaneously — it would be steady losses over a few years. Presumably, most of the employees already learned how to code, and so might be able to find jobs elsewhere. One of the major capital expenditures would be chips for “mining” rigs and servers, but given that demand is outrunning the supply of chips, this would probably be a net benefit for production — firms that were unable to produce goods due to chip shortages would be free to ramp up production.

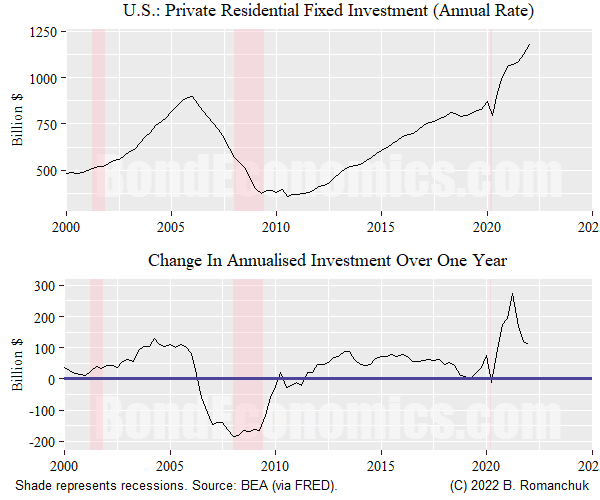

The figure above illustrates the scale issue. I have picked an important industry in the United States whose fortunes are tied to financial markets: residential construction. The top panel shows the level of (annualised) fixed investment, and the bottom panel is the change in spending over a year. (Technical note: the investment figures are quarterly figures at an annual rate. If we wanted to show “investment over the year,” we should use the 4-quarter moving average of the above series. I wanted this non-smoothed series because it is scarier.) In a typical recent non-volatile year, the change in spending runs at about $50-100 billion — and that is just one (major) component of total economy fixed investment in one (major) economy. I am unsure how much the crypto industry spends on wages, bribes, and equipment in a year, but I see no evidence that it would be anything other than a rounding error when compared to expenditures in industries run by grownups.

This is different than the technology crash that took place around the year 2000. Although there were dubious web companies with huge market capitalisations and a half dozen employees, there were tech firms that had a huge spending footprint: telecom equipment suppliers and the telecom industry. Working from memory, the European incumbent (i.e., privatised state monopolies) telecom firms spent 100 billion euros on 3G licenses, and a larger amount on the infrastructure buildout. Unfortunately, the debt markets started to barf all over telecom paper, and the spending spree dried up — which then whacked the high-flying communications equipment manufacturers.

Market Cap A Hypothetical

The main reason to get excited about crypto collapses are the drops in market capitalisation. However, the market cap is just the price of the last trade — which might be a tiny quantity — times the notional outstanding. Since the whales know they need to hold to allow prices to rise, the free float of a non-pegged crypto asset is going to be most of its outstanding. (Trading volume can easily be the same small portion of the float being turned over rapidly.)

Take an extreme (and unrealistic, to keep the math simple) example: a small group could create bogus orders in an illiquid asset with 1 million units outstanding, and trade a single unit back and forth until the price doubles from $100 to $200. There is a market cap increase of $100 million, but only a single unit with a value of at most $200 was being sent back and forth. The market capitalisation increase is orders of magnitude greater than the actual transactions.

One might point to the elusive “wealth effect”: the holders had an increase in paper wealth. However, this only matters if behaviour changes. There are two mechanisms for this.

People/firms borrow against their crypto holdings. Anecdotally, this is happening, but it is unclear to me that financial firms are willing to give loans collateralised by the full market value of crypto holdings, and the amounts involved are small when compared to something home equity lines. If prices fall, this mechanism would result in forced liquidations. In any event, these borrowings are used to buy financial assets, which does not affect GDP.

Savings rates drop as a result of increased wealth. Once again, this is happening, but it is unclear how large the effect is. From the perspective of latecomers to crypto, the anecdotal evidence points to an effect that is the opposite of what is predicted by models: they increase their savings into the asset when the price rises, then stop once the price falls.

Since holders of crypto assets are international, we would need to compare the hypothetical wealth effect to the combined GDP of the holders’ countries. Even if we took a high end (implausibly high, in my view) estimate of the wealth effect multiplier at 5% ($1 increase in market cap raises spending by $0.05), the “wealth effect” of $1.3 Trillion in crypto wealth evaporating (estimate taken from https://coinmarketcap.com/) is $65 billion. This is not enough to cause a recession.

There has been a transfer of wealth from new entrants to early adopters, and the new entrants would need to rebuild their retirement savings. That process would be slow, and not a driver of the business cycle.

Summary: Other Things Need to Go Wrong

To get a recession, other things need to go wrong beyond crypto. The energy price spike is providing us one candidate, particularly for economies outside North America.

I will now discuss “stable” coins.

Two Models For Stability and Liquidity

The crypto universe mainly consists of technical people attempting to re-invent wheels that developed in finance decades/centuries earlier. One things that they have re-discovered the great mismatch between borrowers and lenders: lenders want ultra-short maturities (i.e., “liquidity”) with high interest rates, and borrowers want long maturities with low interest rates. Traditional finance accommodates these incompatible demand by having a range of financial products, with high liquidity ones offering low returns, and returns increasing as the maturity increases. (Equity is the limit of this: highest expected returns, infinite maturity date).

Although a fiat currency issuer has no problem with providing liquidity, the private sector is not in a similar position. There are two main models for providing the ability to withdraw funding on demand: banks, and money market funds.

Most popular commentary on banks obsessively focuses on bank deposits and loans (because of a “money” fixation), banks have an entire balance sheet. They hold liquid securities on the asset size, have access to credit facilities (often from the central bank, but otherwise “senior” banks), and issue term deposits. bonds, and equities. This means that they are “over-collateralised” if we looked at their deposit liabilities alone.

Money market funds match assets to liabilities (investor unit holdings) on a 1:1 basis. Retail-facing money market funds are regulated, and constrained to hold “liquid” securities, and use a special accounting treatment that allows them to keep their unit values at a “par” value. (I worked on the analytical support for a money market fund that was held by institutions. Investment restrictions were somewhat self-imposed, and the accounting treatment was not really my concern.)

“Stable” coins in crypto generally attempt one of these two strategies: either over-collateralisation (like a bank), or a money market fund structure.

Over-collateralisation works on the assumption that there are buffers in less senior liabilities (including equity) that allow for a variation in asset values without the value of assets dropping below the value of the senior liabilities whose value is pegged. Whether this is credible depends upon one’s beliefs about the risk models being employed.

Bank Runs

For something like a money market fund, there is very little room for risky assets. Let us imagine a fund that wants to peg its unit value at $1, has 10,000 units outstanding, and has $9,000 invested in a no-risk liquid asset, and $1,000 in a illiquid risky asset.

Let’s then assume that the risky asset value drops by 20%, which puts the value of the assets of $9,900, giving each unit a fair value of $0.98. If the fund sells the liquid asset to redeem its units at par, the investors redeeming get a profit versus fair value — at the cost of the investors who hold. We can then see what happens if investors redeem 2,000 units at a time.

After the first withdrawal, there are 8,000 units backed by $7,800 of assets, dropping the value per unit $0.975.

After the second, units drop to 6,000, and the per unit value is $0.9667.

The third drops the per unit value to $0.95.

The final tranche is liquidated at a value of $0.90. These unit holders ate all the losses to benefit the unit holders that exited.

If investors see that such a situation is developing, the rational response is to redeem units to avoid being the final holders that eat the losses — akin to a “bank run.” The first rule of a panic is to panic first — in this case, the earlier you liquidate, the higher the per unit asset value.

Stopping a “Bank Run”

The only way to avoid breaking a pegged unit value if the portfolio value drops below the peg is to inject enough new funding to meet withdrawals. If liquidation is avoided, the yield on risky assets might overcome the earlier losses.

Where do the inflows come from?

New investors that are unaware that asset value dropped below the peg value. In a traditional money market fund, investors move into and out of the fund in an irregular fashion, and the accounting smoothing is normally enough to cover up issues.

Parties close to the fund will inject new funds at par. Since management of the fund is presumably profitable (why create it otherwise?), such an injection is rational, at least within limits. There might also be an incentive to avoid the fund liquidating its positions.

Investors might lend against assets with a valuation haircut. This would cut into future interest income (since the borrowing rate is presumably high), and reduces the backing of unit holders further in a liquidation scenario. This is normal practice for banks, but would be more awkward for a money market fund.

Other than the fortuitous possibility of new inflows, all of these possibilities involve somebody taking a loss — operators injecting capital, or unit holders being subordinated by new financing. A segment of the crypto industry appears to have convinced itself that it was possible to create a fund with a magical ability to avoid such losses: the structure would mint new tokens to cover the loss.

This brings us back to a fairly basic valuation question: if an entity can mint tokens at no cost to recover losses, why not print infinite amounts to get an infinite amount of free value? Does that not appear to be a free economic lunch? In the case of BTC, the defenders argued that the finite number of tokens meant that there was no free lunch. In other cases, this question was dealt with by assuming nobody would ask it.

My impression is that stable coins are being forced to evolve to match the two existing traditional models for managing pegged asset values. That said, without robust controls on manager behaviour, accidents can still occur.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete