The passage that caught my eye was as follows.

There have been few, if any, instances in which inflation has been successfully stabilized without recession. Every U.S. economic expansion between the Korean War and Paul A. Volcker’s slaying of inflation after 1979 ended as the Federal Reserve tried to put the brakes on inflation and the economy skidded into recession. Since Volcker’s victory, there have been no major outbreaks of inflation until this year, and so no need for monetary policy to engineer a soft landing of the kind that the Fed hopes for over the next several years.

I have also noted that recessions bring down inflation, which might be seen as obvious. However, there is a bit more to the story. My argument is that we need to ask ourselves: what do we know for sure about inflation? The empirical observation that it normally falls after recessions is one of the key “stylised facts” that we can work with. The problem is that we rapidly run out of stylised facts after that point. As a result, I have a suspicion of elaborate mathematical theories about inflation.

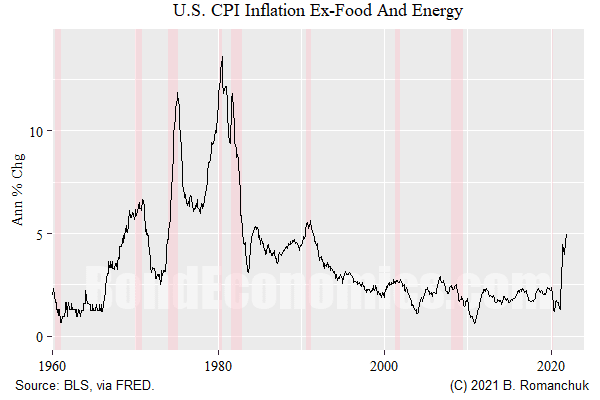

From the perspective of Larry Summers, that is an awkward position. After all, he is one of the standard bearers of neoclassical macro. Surely the decades of DSGE research managed to advance economic theory beyond a stylised fact that jumps out to anyone who looked at a chart of inflation with recession bars (figure above)?

I have been reading about the power of expectations from neoclassicals for a long time. At one extreme, we have economists claiming that the central bank can force nominal GDP to follow a particular path almost entirely relying upon the expectations fairy. There are thousands of turgid articles debating the optimality of various monetary policy rules, such as average inflation targeting. Meanwhile, we have a top professor from Harvard effectively throwing all of that into the waste basket, arguing that we need a recession to lower inflation.

Admittedly, one could argue that my interpretation is a stretch. One angle is that Summers deliberately simplified his arguments — which is necessary for an op ed. The problem is that even I can offer popularised versions of theories without saying the opposite of what I really mean. The other angle is that Larry Summers was angered by being passed over by the Biden administration, and he is just throwing anything he can at the wall and hoping it will stick. Even if we grant this, it is interesting how he has abandoned discussions of expectations.

Another interesting angle to his piece is that he sticks to conventional theory in another place in a way that is not matched by most of the neoclassical commentators (although I ran into one or two exceptions). He argues that real interest rates matter, and so the inflation spike coupled with fixed nominal rates has been impressively stimulative. (His worries about secular stagnation and the policy rate being permanently stuck below r* have left the building.) This is of course what neoclassical models suggest, so one might wonder why this is not remarked upon more widely. The Fed could hike rates by hundreds of basis points, yet the real rate would still be below historical averages.

Although it is common to see the sentiment that the economy will careen out of control as a result of falling real interest rates in financial commentary, it has been rare to see academics discuss this property of neoclassical models — presumably the result of the stability of core inflation since the early 1990s. I have not been paying close attention, but the various estimates of r* blew up in 2020, and sooner or later, some neoclassicals will need to try to come up with a new estimation technique. Those estimates might be interesting, although I suspect that the estimation technique will be chosen to give the desired theoretical outcome.

This leads into my feeling that aggregated macro theory has not been particularly illuminating since the pandemic hit. Most of the interesting work has involved digging into data, and trying to understand why heavily analysed aggregated series are behaving the way they are. Attempting to understand the economy as the result of the optimising decisions of some representative households is not getting one very far. One recent article by the New York Fed about their model forecast offers an example of the issues faced. I only scanned the article, but if we look at the inflation/growth forecasts near the end, we see that the model forecast is for a reversion towards historical means. Although that is not wildly different than my forecast, the reality is that such mean-reverting behaviour is built into the model, and so I do not take much comfort from the model matching my biases.

Holiday Publishing Pause

It looks like this will be my last piece ahead of Christmas. I got hit by some non-COVID minor malady a little while ago, and so I am now catching up on other things. I wish all my readers a happy and safe holidays!

I don't even know if my question makes any sense, but is inflation REALLY worse than recession? What would be the incentive to choose the latter over the former?

ReplyDeleteOr does the answer depend upon who you are, how (or whether) you are employed, whether or not your income is earned or unearned and so on? Which is to say, does the answer really depend upon power, class and politics?

There is an exaggerated fear of inflation, yes. However, I doubt that recessions can be avoided forever.

DeleteAlthough inflation typically falls in a recession, it is presumably not necessary to get it under control.

Great post - but one bone to pick.

ReplyDeleteOne thing we've heard both in the 2008 crisis and the current one is the complaint that macroeconomic models (DSGE or otherwise) can't predict crash-level shocks or, more validly, that they don't work or aren't informative during crisis. As to the first, of course standard can't predict crisis. Dynamic models have to have either stable or unstable tendencies. Models that included doomsday would would likely be useless for "everyday." Like bearish analysts, they would predict 20 of the next two disasters.

But on the second criticism, well, yes, a crisis can quickly show how a class of models is critically incomplete. The absence of a financial system in pre-2008 DSGE embarrassed the macro profession hugely and reduced its credibility in lasting ways.

But I think there is a second reason that macro models don't work well in crises. Brian points out that "estimates of r* blew up in 2020," and my response is "of course they did." Normal-times model calibrations don't hold true is a large economic crisis, precisely because the the economy, in such periods, is recalibrating itself. The fact that, as in the US, real GDP has recovered almost to former levels and possibly returned to trend doesn't mean that we have returned to the "same economy" that prevailed in the long, comparatively eventless recovery from 2008. Equilibrium values like r* and u* could be very different today than they were in February 2020. Then, with US employment rates at historic lows and inflation both low and stable, economists were marveling at how low u* must be and "run hot" enthusiasts seemed completely vindicated. Today, with the US economy facing supply constraints and inflation grabbing headlines, both r* and n* could be above the current policy rate and actual current unemployment.

The key word in my last statement was "could". I'm not saying that NAIRU is above the current unemployment rate; I am saying that the position of policy hawks like Summers is not entirely perverse.

Finally, you don't have to "believe" in DSGE models or "*" equilibrium variables to consider the point that we can't simply extrapolate back to February of 2020 to compute our policy goals. February 2020 isn't recoverable. Our new "normal" economy will be different and will possibly have very different policy requirements - even if the current burst of inflation turns out to be more transitory than not.

Largely agree with this. As for your point “ Normal-times model calibrations don't hold true is a large economic crisis, precisely because the the economy, in such periods, is recalibrating itself. ”, the theory is that DSGE models are supposed to be based on “deep structural parameters.” I am not convinced, but that is the standard response.

Delete